Movies

Women in tech history: Hedy Lamarr — Hitler, Hollywood, and Wi-Fi 📽️

This is the sixth article in a series about amazing women in tech history. Previous entries have featured Margaret Hamilton, Grace Hopper, the ENIAC programmers, Katherine Johnson, and the women of Bletchley Park.

Today’s entry is a bit of an anomaly. We’ve covered some inspiring women in this series but most of them aren’t well-known to the general public. This is particularly true for the ENIAC programmers, who were forgotten for most of their lives; and the women of Bletchley Park, who had to keep their life-saving work secret for 30 years. Hedy Lamarr, on the other hand, was a household name in the western world. She was the highest-earning woman in Hollywood at the peak of her acting career and was often described as the most beautiful woman in the world.

Photo: Publicity photo for Comrade X, public domain.

Lamarr got her biggest parts in movies because of her looks, which is something she regretted all her life. She became typecast for her glamour and was given few lines compared to the men she starred with. She had a creative and scientific mind and was described as someone who always came up with solutions to problems. Many people in her life didn’t actually know this about her because they made assumptions based on her appearance. Can someone be eye-candy and smart? The sexism of Hollywood drove her to be creative in other fields and she went on to invent technology that has almost certainly influenced your life.

Having Hitler for dinner

Hedy Lamarr was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in Vienna, Austria, in 1914. Lamarr began acting at a very young age and small parts in theatre productions as a child. She was eventually spotted as a teenager by German producer Max Reinhardt, who brought her to Germany to train in theatre but she soon entered the film industry. Lamarr was only 18 when she starred in Ecstasy, a controversial 1933 film where she played the ignored wife of a distant husband. This role made her famous in Austria but not necessarily for the best reasons. It was seen as controversial for showing such a young woman naked and faking orgasms.

Photo: Publicity photo for Comrade X, public domain.

In 1933, the same year that Ecstasy had brought her so much attention, Lamarr married one of the richest men in Austria: Friedrich Mandl, a munitions manufacturer and merchant. Although half-Jewish, he supplied weapons to Mussolini and had close connections with the Nazis. Together they lived in a huge castle and held parties there with the likes of Mussolini and Hitler. Even by the age of 18 her life was far from ordinary.

According to Lamarr, Mandl was a jealous, controlling man and didn’t want her to continue acting for fear she would star in something like Ecstasy again. She was kept in the castle and described feeling like a prisoner. Most of her social interaction was with fascists as she was forced to accompany Mandl to his business meetings. This was a difficult time for Lamarr but there was a positive to take from it all. Many of the meetings were with military scientists discussing advanced technologies and it fascinated her. This was when she began to focus some of her time and resources in science and apply her natural creativity to fix real problems.

The escape

In 1937 Lamarr couldn’t live in that castle any longer but was sure Mandl wouldn’t allow her to leave. According to her autobiography, she disguised herself as a maid and sneaked out. She didn’t just want out of the castle, she wanted to be as far away as possible. She made her way to Paris where she met MGM head Louis B. Mayer, who was scouting for foreign talent. He convinced her to come with him to America to star in Hollywood films.

Photo: Hedy Lamarr in Lady of the Tropics. Trailer screenshot, public domain.

From 1938 to the late 1950s Lamarr dominated Hollywood. Much to her displeasure in later life, she wasn’t necessarily loved for her acting abilities or personality but for her looks alone. She was seen by many as the world’s most beautiful woman and the marketing directors recognised this so they played into it. Her foreign accent and mysterious stage name only added to the image that made her the pin-up of choice for many soldiers fighting abroad.

Lamarr seemed to have it all. She was rich, famous, and admired. But in many ways she was still a prisoner. Much like she felt trapped by Mandl and his castle, Hollywood trapped her because of her looks. She was increasingly given roles that were highly sexual with very few spoken lines. She became typecast in such a way that she appeared to many as a face rather than a person. She obviously knew there was more to her than eye-candy and this attitude sometimes caused problems with executives.

I was the highest-priced and most important star in Hollywood, but I was “difficult.”

She grew bored and needed another outlet for her creativity. With World War II on everyone’s mind and exciting technological advances happening at the same time, her interest in science was stronger than ever. She wasn’t given the freedom to invent anything on screen so she took to inventing things in the real world.

Frequency-hopping

Lamarr spent years working on inventions, many of which were successful in the fact that they worked but didn’t necessarily go anywhere commercially. These includes improved traffic lights, improved tissue boxes, and even a pill that turned water into a carbonated beverage. She had been interested in torpedoes and radio technologies since her time in Mandl’s castle, hearing scientists talk about the weapons on Nazi U-boats. During World War II, she turned her attention to inventions that could help in the fight.

She knew from those meetings that remote controlled torpedoes weren’t a good option because radio-jamming could protect Nazi boats. As long as you knew the frequency, you could disrupt the signal to the torpedo. She puzzled over ways to protect torpedoes and hit upon a solution when she met the film composer George Antheil. He used strange instruments and arrangements in his music and liked to tinker and invent much as Lamarr did. She was inspired by his use of multiple pianos roles to move music from one piano to another without missing a beat.

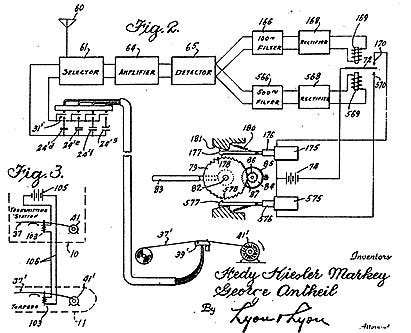

Image: A figure from the 1942 patent. Via Flickr/Floor, distributed under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

Together, they successful patented a genius technology, frequency-hopping spread spectrum (FHSS), which would use the piano roll to protect radiowaves from being jammed. Just as the music could transfer from one piano to another by carefully synchronising the piano rolls, radio signals could be switched to other channels using the same method. By doing these switches in a pseudorandom order known only by the transmitter and receiver, it would be impossible for the Nazis to jam or read the signal. At best they could jam one frequency but the torpedo would only be out of communications briefly until the next frequency hop.

The patent was made on 11 August, 1942, but the Navy turned it down. They didn’t fully appreciate its value, the technology would be difficult to implement, and they were reluctant to use patents that didn’t come from within the military. In the 1950s the technology was taken by engineers at Sylvania Electronics Systems Division for in military communications and by the 1960s an upgraded version was indeed being used to control torpedoes.

It’s all around us

Frequency-hopping spread spectrum is one of the most important aspects of Code division multiple access (CDMA), which is in many technologies we use today. One of its first is in GPS, which you use every time you check your location in your smartphone’s maps app. Mobile phones also used CDMA for phone signals and if you’ve ever downloaded something over a 3G network you were using technology built around Lamarr and Antheil’s invention. With frequency-hopping spread spectrum technology being all around us, it’s easy to take it for granted, but the invention should be admired and respected for being so creative and ingenious.

Despite the work influencing so much technology that dominates our lives, they never received much recognition for the work. Lamarr didn’t receive any money for the use of her patent by the Navy or by phone companies. Like many of the women in tech history we’ve written about, Lamarr was largely ignored for most of her life when it came to science and technology. Now there are a few books about her life and movements to get her recognised. The latest project was a documentary about her life to be filmed by Reframed Pictures. Here’s Susan Sarandon talking about the project:

People started to make the connection between the Hollywood superstar and frequency-hopping in the 1990s. In 1997 she finally received recognition for her work when the the Electronic Frontier Foundation gave her the Pioneer Award. According to her biographer Richard Rhodes:

When they called her up to tell her she would get the award her first words were, Hedy Lamarr being Hedy Lamarr, “Well, it’s about time.”

Lamarr was in her 80s when she received this recognition then died shortly after of heart failure in 2000. In 2014 both co-inventors of the technology were inducted into the US National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Scared money

Lamarr didn’t think she was necessarily smarter than people around her. Instead, it was her attitude that set her apart. She asked questions. She wanted to improve things. She saw problems and knew they didn’t have to be problems. Some people in her life saw it as the wrong attitude and she was often criticised for being a difficult star. But Lamarr was doing exactly what she wanted to do so was clearly winning. And how did she win? As she said in Popcorn in Paradise:

I win because I learned years ago that scared money always loses. I never care, so I win.

“Scared money” refers to being so afraid of losing that it impairs your decision-making and makes it more likely that you will lose. Lamarr was able to let that go. She had the world’s eyes on her just waiting for a mistake yet she made it in Hollywood and when that didn’t appeal anymore she contributed to technology you’re likely using while reading this. She was beautiful, smart and talented but none of that guaranteed success in male-dominated fields. What mattered most was that she wasn’t afraid.

Lamarr faced sexism like all the women in this series but in arguably more unusual circumstances. She wasn’t just a woman in tech; she was also a superstar admired for her beauty. According to Lamarr, this meant she faced two very different sides of misogyny. Some people assumed, from looks alone, that she wasn’t smart. Others assumed that if she was smart then it was a negative aspect of her personality. Her smarts were likely a devious, deceptive, untrustworthy intelligence and this was a problem rarely said about attractive male leads. Sometimes you just can’t win, except she eventually did. She won because scared money always loses and she wasn’t afraid to be herself.

This is the sixth article in a series about amazing women in tech history. Previous entries have featured Margaret Hamilton, Grace Hopper, the ENIAC programmers, Katherine Johnson, and the women of Bletchley Park.

Who is the Blade Runner? 📽️

I’ve always known that there’s debate over whether Deckard is a replicant or not in the movie Blade Runner. I’ve never understood the debate because I feel the film spells it out pretty clearly. I figured some of the disagreement stems from people watching different versions of the film or the fact that some people just don’t pay much attention. I have friends who have movies as background entertainment, which is something I can’t do.

Today I was talking with a friend who had recently seen the best version (Final Cut, which is the true director’s cut) and they didn’t think Deckard was a replicant. So I explained why, in my opinion, he definitely is. I was surprised to find that two other friends, who also agree Deckard is a replicant, didn’t interpret the film the same way I did. I started asking my film friends online (ones I knew had seen the Final Cut) and none of them interpreted the film the same way I did.

I was a bit worried that I had read the film wrong. I took to Twitter and apparently only a small minority of followers seemed to know what I was talking about. So now I feel I have to dump these thoughts from my brain but I didn’t want to share all this in the Twitter thread because spoiling amazing films on social media isn’t a great idea. So here we go. Spoilers ahead. Seriously. Blade Runner (Final Cut) is a sci-fi masterpiece and really should be watched without spoilers so pleeeeeeeease watch it first before reading more. Here’s a nice picture before the spoilers begin.

Who is the “Blade Runner”?

The question “is Deckard a replicant or not” has always baffled me because it’s answered. To me the real question of the film that is eventually answered is “who is the Blade Runner?” I’ve always thought this was super obvious but the blade runner isn’t Deckard; it’s the ex-blade runner, Gaff. If you’ve forgotten who Gaff is, here’s a picture:

Yep, Gaff played by Edward James Olmos (also of Battlestar Galactica fame, so say we all). He is the super blade runner. The best there is. A legend. Let’s just be up front and tell you exactly what I thought was common knowledge by the end of the film: Gaff is the best blade runner but he’s getting older, he has a bad limp now and uses a cane, and just isn’t the “old blade runner” anymore.

What’s more, Tyrell can now create replicants who literally think they aren’t replicants by implanting them with the modified memories of real people. Rachel has the memories of Tyrell’s niece. I’m mostly ignoring the previous versions of the film but the original does mention that Gaff had been hanging around the Tyrell place and knew about Rachel. Of course he does. His memories have also been used in a replicant: Deckard.

“I need the old blade runner, I need your magic”

Blade Runner doesn’t have many characters who aren’t important to the plot. Sure there are extras roaming the streets but named characters with dialogue play an important part in the story. Except Gaff, apparently. He sits around and makes origami figures. But I think he’s the most important character in the film. The first time we see him he collects Deckard from a noodle bar. Unless Deckard has a tracker on it’s a bit weird that they find him there rather than his house or by calling him. Gaff knows where Deckard will be. This isn’t the last time Gaff appears to know what Deckard knows.

Next we see Gaff in the background as Deckard’s boss tries to give him an important assignment. Gaff doesn’t speak. He seems to have no role except to observe. It’s almost like he’s supervising. Or a backup if anything goes wrong with Deckard. I’m of the opinion that Gaff can still handle himself with a replicant. But four extremely dangerous models all at once? Sounds a bit much. When Deckard is refusing to take the assignment, Gaff knows he’s scared. Why? Because he’d be scared. Gaff knows Deckard better than anyone. That’s when he makes the first of his origami figures: a chicken. He also makes a man with a penis when Deckard is falling for Rachel and there’s the origami at the finale that we’ll get to. Is Gaff some kind of psychic?

There’s also a line from the boss that just stood out to me like a sore thumb. He seems excited and desperate to get Deckard on this case. Perhaps it’s a slip of the tongue but he says “I need the old blade runner, I need your magic”. Gaff, the best blade runner, isn’t his old self anymore. But with his memories in Deckard, maybe the old blade runner can be back in action?

“You’ve done a man’s job, sir!”

Gaff continues to keep an eye on Deckard, supervising him. It’s hard to know in the early stages of the film if this is a safety precaution in case Deckard figures out he’s a replicant or if Gaff is curious and sympathetic. But throughout we get hints that Gaff knows a creepy amount about Deckard. He knows where he’ll be, knows his emotions… and there are even more subtle clues but I won’t share too many because some could be coincidences. My favourite one that can’t be a real clue: I used to sell magic tricks for a living and the context I know the word “gaff” from is a gaff deck, a trick deck that looks like an ordinary deck of cards but is more than it seems. I’m sure it’s a coincidence rather than a hilariously clunky clue that the two characters are Gaff and DECKard!

But the film is full of hints that Deckard is a replicant. His journey through the film, discovering that Rachel is a replicant, reflects our own journey as viewers learning that Deckard is. We’re introduced to Gaff first. We’re then introduced to the idea that replicants can think they’re human. We learn about false memories (and in some versions that Gaff has some involvement with the people who do this). Deckard comes to sympathise with Rachel and learn that replicants can feel and be loved, and we’re simultaneously learning this about Deckard. A really cheeky moment is when Rachel asks Deckard if he’s ever been tested himself and he falls asleep before he can answer. And that is the answer. It’s right there. If you want to know for certain if all these hints mean anything you have to look at that answer: his sleep.

Deckard has a recurring dream of a unicorn. There aren’t other unicorns in his life that we’re aware of. As viewers we are privileged to see Deckard’s dreams and know something that nobody else in his universe can know. We’re literally seeing into his mind. He dreams of unicorns. We learn this information and store it for later.

At the excellent climax of the film, the first person Deckard sees after Batty dies is Gaff. The original version of the film was very heavy-handed with its narration and also clues. For the better versions they removed the narration and some of the dialogue that made the plot too obvious. One of my favourite removed lines was Gaff’s compliment to Deckard: “You’ve done a man’s job, sir!” Oh my god, what a loaded line. Sure, he’s done a good job. And a man’s job. As opposed to what, a replicant? And not just any man’s job, but a specific man’s job! It works in so many ways.

Origami

But even then nothing is really confirmed. Gaff is always around, always supervising dealings with Deckard, always knowing where he’ll be… but it doesn’t confirm anything. Perhaps Gaff just has intimate knowledge of newer blade runners for professional reasons. But by this point of the film we also don’t have a solid explanation for why Gaff makes a chicken figure when Deckard is scared or a man with a penis when Deckard is talking about Rachel. That’s a little too intimate. Does Gaff know what Deckard is thinking? Yes. He knows because it’s what he’s thinking. Nobody knows Deckard like Gaff does. Actually, he even knows what Deckard dreams about because they share the same memories and dreams.

Gaff chooses to warn Deckard at the end of the film. He warns him to save Rachel and perhaps even protects her because he was at the apartment at the very end of the film. Then the film drops its big reveal: Gaff leaves his final origami figure for Deckard to find. A unicorn. The thing Deckard sees in his dreams. Why Gaff chooses to help Deckard isn’t explained. Maybe he becomes sympathetic for Deckard just as Deckard does for Rachel. It should be no surprise that they come to the same conclusion about the lives of replicants given that they’re more or less the same person. Deckard saves Rachel and Gaff saves them both.

This is my favourite thing in the film. The dream is such a great misdirection. Halfway through the film we see the dream as proof that Deckard is human. It throws us off the scent. I mean, do androids dream of electric sheep? But by the end it’s literally the answer to the big question of whether Deckard is a replicant or not. That’s how I’ve always interpreted the film from the first time I saw it. I really can’t imagine seeing it any other way or Gaff would just be pointless. So there you go. I’m glad I got that out of my brain and onto the internet. I’m 100% positive others interpret the film the same way I do. They must do. But I’ve just been shocked at how many of my friends don’t see anything in Gaff when watching any of the versions including the Final Cut.

P.S.

I’m adding this short section just to address the reactions to this piece. I predicted I’d see a lot of people saying “oh wow yeah I know Deckard is a replicant but I never really thought about Gaff before except that he’s odd” and that is the most common reaction I’ve received. This piece is about Gaff, not about Deckard being a replicant. But I’m still getting reactions from people saying they think Deckard is a human and I’m not really understanding how they can explain that. You have another character aware of Deckard’s dreams. You have the director of the film confirming that Deckard is a replicant and that the unicorn is the reveal. And you have all the extra scenes that were cut because they would make it far too obvious. Try this alternative ending, for example:

“Did you know your wife for a long time?” is interesting because he answers “I thought I did”. It was actually Gaff that knew her. But more importantly this ending would make the very last lines of the film be: “We are made for each other”. That’s way too corny and heavy handed. I’m a big fan of how all the answers are in the film if you look for them but it’s much more subtle. I’m a huge fan of how making Deckard dream seemingly gives us proof he’s human early on and that someone else knows his dreams simultaneously shows he isn’t and makes the end of the film a callback to the title of Dick’s great book.

I think the real issue here is that Deckard is a human in the books and there’s a chance that Deckard may have been envisaged as a human in earlier versions of the film. I feel the character was always written to begin questioning it himself but in a subtle, vague way. So whether you think Deckard is human, or a replicant, or even perhaps the answer depends on the version you’re watching, you’re always supposed to at least have a suspicion and Deckard is always meant to have a vague sense of it regardless of the answer.

I’ve also had two reactions to the new film coming out. One is from people who feel Deckard is a replicant saying they were disappointed to see he’s still alive and that this is wrong or means they were wrong. The other reaction is from people who feel Deckard is a human, pointing to the new film as proof since he’s still alive. Remember, replicants live for four years.

So I hate to keep dragging you back to the original narrated version of the film because I don’t like how heavy handed it is but these are Deckard’s last narrated lines: “Gaff had been there, and let her live. Four years, he figured. He was wrong. Tyrell had told me Rachael was special. No termination date. I didn’t know how long we had together… Who does?”

Replicants live four years because they’re designed that way and you can’t change it or extend that life. But Rachel was designed to live longer. She’s special. She also differs from normal replicants in that she has the memories of a human (Tyrell’s niece). A replicant that has someone else’s memories and no forced termination date? Right there in the movies themselves? Maybe not so weird that Deckard is still alive in the latest film, huh?

Some thoughts and disagreements on The Matrix as a trans allegory 📽🏳️🌈

This post was originally published on Medium in 2017.

Late in 1999 I was feeling pretty lost. I had a good life by most measures but something was wrong. I’d felt it since childhood but when puberty hit, it went from “feeling different” to “the bad feeling”. Whenever I tried to bring it up with someone I was made to feel disgusting or broken. I’m transgender but back then I didn’t even know what to call it. Were there others like me? Was there something wrong with me? Few things seemed to help but distractions such as videogames and films allowed me to briefly escape my feelings. In late September 1999 I rented a new sci-fi action film everyone was talking about. I pushed the tape into my trusty VHS player, huddled up in bed, and watched The Matrix for the first time.

In Neo I immediately saw a reflection of myself but I didn’t immediately read much into it. When you’re trans it’s easy to find characters to identify with because the transgender experience is a very human experience. A lot of trans people find characters to relate to in Disney, simply because many of their stories handle identity and being your true self. I saw Neo feeling lost, knowing that something was up but not even knowing what to call it. He would stay awake for hours at night on his computer, searching for answers, wondering if anyone out there felt like he did. I thought “here’s a character who feels lost like me” but I didn’t read more into it than that. Then the next scene spoke to me too. And the next. I started to have an unsettling feeling that this film knew more about me than I did, much like Neo watching someone else’s words flash across his computer. “Knock knock”. I’ve related to characters in films before but I got an eerie sense that The Matrix was created just for me. My heart was racing when Neo finally met Morpheus. Imagine baby trans Jen taking this in:

“You’re here because you know something. What you know you can’t explain, but you feel it. You’ve felt it your entire life, that there’s something wrong with the world. You don’t know what it is, but it’s there, like a splinter in your mind, driving you mad.”

What if I told you (in my best Morpheus voice) that The Matrix is a trans allegory touching on themes such as denial and acceptance of gender identity; trans erasure in death; the diversity of transition experiences (not everyone uses hormone therapy, others even regret transitioning etc); and that trans activism and education are necessary if we want to live in a peaceful world?

In the words of Neo…

Art isn’t static

The Matrix was written and directed by two trans sisters, Lana and Lilly Wachowski, who have stated that trans themes appear in much of their work but nowhere as obviously as in The Matrix. When asked about fans looking back at the film, with new knowledge that both creators are trans women, Lana Wachowski once said that “art isn’t static”. I couldn’t agree more and this gets to the heart of why I want to write this piece.

Viewing art with a fresh pair of eyes can be like experiencing it for the first time all over again. Consider the many different perspectives people could have when viewing The Matrix. It’s obvious that a cisgender person (someone who isn’t trans - these are Latin prefixes), will likely interpret the film differently than a trans person would. Perhaps you may interpret the film differently before compared with after learning that the Wachowskis are trans women. That said, some people can’t see it at all:

For me, always watching as a trans person, the interpretation of the film has evolved just as I have over the years. Art isn’t static. Of all the themes and metaphors you will read in this piece, I think I recognised about 25% of them during that very first viewing in my bedroom as baby trans Jen. I saw things that my friends didn’t, because they had no trans experience whatsoever. Over the years I’ve gleaned more and more from the film because of my own personal journey. As I grew up I learned trans terminology; I learned there were others like me; I learned about hormone replacement therapy; I learned about haters, chasers, and allies. As my own trans experience evolved, I noticed more of the trans allegory in scene after scene until the film became a living, breathing thing that changed alongside me.

Another reason for emptying these thoughts onto the internet is because I disagree, on many points, with others who have covered it before. I read some of the characters and scenes very differently. More importantly, I don’t think the trilogy has been given enough attention as a trans allegory. When viewed as generic sci-fi action films, the sequels really don’t do the original justice. As a trans allegory, however, they build on the original brilliantly and I think the people who miss the allegory also miss what makes the sequels interesting. Indeed, I believe many aspects of the sequels don’t make sense unless viewed as a trans allegory. I believe this is worth looking at closely and discussing further.

In order to share what I’ve taken from the film I need to provide a little perspective, so this piece necessarily has to touch on personal stories too. My goal is to give you some insight so that you (especially if you’re cisgender) can empathise and see why the film speaks to me and many other trans people. This might not be your average film analysis (actually it’s best to just consider this venting) but stick with me and and I’ll show you how deep the rabbit-hole goes.

Plugged into the cis-tem

Neo is obviously at the core of The Matrix. In the trans allegory, his journey to become “the One” is also his journey to become his true self. Whether you’re following the sci-fi plot or the trans allegory, Neo starts by knowing there’s something up, though he doesn’t know exactly what. There’s definitely more to his world. Then he comes to learn what he is by meeting other people who also felt the way he does. That doesn’t necessarily mean he accepts it or fully believes it himself. He has forces in his life that believe in him and others that threaten him, but through struggles Neo comes to accept himself and who he really is. This arc, taking Neo from discovering the truth to accepting his identity, takes place over the entire first film. The sequels handle the necessity of activism, the diversity of transitioning experiences, and peace.

“The Matrix is a system, Neo. That system is our enemy. But when you’re inside, you look around, what do you see? Businessmen, teachers, lawyers, carpenters. The very minds of the people we are trying to save.”

In the film, the matrix itself is one of two worlds or more accurately a world within a world. In the trans allegory, the matrix is simply how society sees gender. The matrix is cis-normative society. As Morpheus explains, that world or way of thinking is all around us. We see it on TV and we see it when we look out the window.

It’s no accident that the matrix was created by machines. It’s artificial. It’s a construct. All the humans living in the matrix are real biological beings trapped into thinking of gender in its most simplistic terms - not recognising trans people, and not recognising gender beyond the binary. Trans people break free from this system, which is represented in the film by our heroes being unplugged from the matrix itself.

“You have to understand, most of these people are not ready to be unplugged. And many of them are so inured, so hopelessly dependent on the system, that they will fight to protect it.”

Importantly, the cis people obliviously walking around in the Matrix are not the enemy; the system is the enemy. There are people out there who say that Black Lives Matters is anti-white, or feminism is anti-men, and that’s obviously bullshit. Similarly, being a trans allegory doesn’t make The Matrix anti-cis. In fact, the allegory paints cis people as victims in this system too and argues that — ultimately — peace comes from understanding and cooperation between trans and cis people.

“It is the world that has been pulled over your eyes to blind you from the truth.”

“What truth?”

“That you are a slave, Neo. Like everyone else you were born into bondage. Into a prison that you cannot taste or see or touch. A prison for your mind.”

The earliest scenes in the film are the most obvious, even to cis people. When Neo begins his journey he is given a choice between the red pill or the blue pill. Many trans people take pills as part of their hormone replacement therapy during transitioning. The fact that assholes online have accidentally co-opted the red pill from a trans allegory created by two trans women is both disappointing and unintentionally hilarious. Side-note: It’s important to note that some trans people don’t undergo hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and they are just as valid as trans people. The Wachowskis address this brilliantly in the sequels and anime projects through Kid, a character who wakes himself up from the matrix without the aid of any pills at all. In the allegory, he’s a trans person who accepts himself and transitions without HRT. He looks up to his trans heroes and he’s one of them without taking any pills. But I digress, we’ll get to the sequels another time.

The Morpheus quotes I’ve been using come from a training scene where Neo learns about agents. It’s extremely powerful but I don’t believe it hits as hard for cis people. The agents are the real enemy. They’re a consequence of the system. They represent fear and hatred of the people unplugged. They’re the oppression of trans people. You can think of them as actual individuals in the sense of transphobic bigots but in the allegory they also represent that fear and hatred as a concept.

I’ve watched many films that openly feature trans people and no other has so accurately captured the feeling of walking down a busy street as a trans person. When I walk into town I know that most of the people around me are good, decent people. Most would probably come and help me if I was attacked or hurt. However, it’s also a fact that an alarming number are hostile to trans people. At best they might ridicule me; at worst they might try to murder me. The terrifying thing is that transphobes don’t have signs hovering above their heads. Until they actually attack, they look just like everyone else. They blend in. When you walk through a sea of people, you have no idea who could really be filled with that hatred, so you have to be ultra vigilant around everyone.

You don’t know who could be an agent.

Trans stories

Neo is the core of the trans allegory but the cast he meets are equally important. Some of them represent aspects of his own journey (especially Morpheus and Agent Smith, who we’ll come to) but other characters tell specific trans stories. There’s Switch, the only character who was specifically written as transgender. She’s the embodiment of the allegory; of being unplugged. Originally the role was to be performed by two actors, one male and one female, to give her a different body when inside or outside the matrix. The sci-fi aspect here is that there’s a glitch in the matrix that left her with a mental projection that doesn’t match her gender. (I’m going to continue using she/her pronouns for Switch because it’s canon now and you know who I’m talking about).

The production companies didn’t like this and had the Wachowskis play down the trans aspect and have the character performed by one actor. The Wachowskis compromised in several ways. Firstly, they hired an androgynous actor, which is probably the next best thing. Most importantly, they kept her character the same. We still know her as Switch, a name that references the switching between bodies as she plugs in and out of the matrix. She even keeps the white clothing while everyone else wears black; a visual queue to help viewers realise the two appearances in the original vision are the same character. Even better, she keeps her original dialogue. Her death scene isn’t exactly nonsensical, but it makes much more sense when you realise that the Wachowski’s engineered a scene in order to talk about trans erasure in death.

Many people come out to find that their relatives and loved ones are unsupportive or even hostile to trans people. It’s also a fact that a scary number of trans people die each year, sometimes from suicide or murder. Sadly, many of these unsupportive families erase the dead’s identity by deadnaming them and ignoring their transness. Obituaries and gravestones show deadnames. This is really common. In the allegory, the Wachowskis give these dead people a voice by engineering a situation where Switch knows she’s about to die. So there she is: back in the world she tried so hard to escape from, and in the body she tried so hard to escape from. Her last words might as well be those of all the trans people who have had their identity erased in death. “Not like this. Not like this.”

The biggest disagreement I have with others is over Cypher, who most people interpret as a chaser. I can see where this thought comes from as he hangs around the heroes, uses them, turns on them, and there’s clearly attraction involved with Trinity. I feel this oversimplifies one of the best characters in the film and a big part of the allegory. I think this view falls down when you consider that Cypher is unplugged, like the others, so he’s a trans person who has transitioned. The difference is that he’s unhappy. He’s jealous of others around him like Neo. And most importantly, he’s filled with regret. He doesn’t like this new world he finds himself in and wants to go back. Just as the sequels bring up more nuanced issues like transitioning without hormone therapy, the original film brings up the fact that there are people out there who wish to detransition.

The most striking parallel with Cypher’s story and our world is that many people who detransition are used by transphobes in order to attack trans people further. People who detransition are seen as proof that there’s something wrong with being transgender or that society is forcing people to transition when they clearly don’t need to. Lo and behold, the agents use Cypher’s detransition back into the matrix to get to the heroes. They capitalise on his struggle. They appear as his allies but ultimately use him to deal a blow to the community he wishes to leave. We’re watching real-life play out on the Nebuchadnezzar.

The worst part of yourself

Not all agents are born equal and Agent Smith plays a special role in The Matrix as both a film and a trans allegory. He’s unique, even as an agent. He still represents fear and hatred of trans people as the other agents do, but for him it’s also self-hatred. As the Oracle eventually explains, Agent Smith and Neo are one and the same. They are flip sides of each other. Two halves of an equation. Equal yet opposite. Agent Smith is a failed “One” while Neo goes on to become successful. In the allegory, Neo eventually comes to accept his trans identity but Agent Smith does not. In some ways you can view Agent Smith as his own person, like a self-hating trans individual, but in almost every scene he also acts as a fearful, hateful aspect of Neo himself.

Being another agent, Smith always represents hostility towards trans people, but he clearly plays by his own rules and has his own purpose. Every action he takes represents Neo’s fear and doubt. Whenever he speaks to Neo, he deadnames him. Always Mr Anderson; never Neo. He captures and tortures Morpheus, who represents the hope and belief Neo has in himself (I’ll get to that). Agent Smith is the part of you that tries to keep you down, sow seeds of doubt, and tell you what isn’t possible. Your failure is inevitable.

Let’s step back from the film for a moment and talk about something that really happened. Content warning: contemplation of suicide. Years before filming The Matrix, Lana Wachowski hit an all-time low in terms of gender dysphoria and willingness to accept herself as trans. She decided to take her own life by walking down into a subway and jumping in front of an approaching train. She fought with herself and at the last moment changed her mind. Down there in the subway, she accepted her identity and from that moment knew she could live a genuine life as her true self. Facing your darkest self in a subway sounds familiar, no?

For my teenage friends, back in 1999, the subway scene was just another great moment of action; but for trans viewers it’s the emotional crux of the film. Neo is being hunted relentlessly by agents and comes face to face with Agent Smith, where he is pinned and appears doomed to be hit by the incoming train. Agent Smith, deadnaming Neo as usual, describes his death as inevitable. The train is coming and one way or another, “Mr Anderson” is going to die.

“My name… is Neo.”

Up until this moment Neo has been struggling to believe in himself and accept who he is. He clearly wants to believe but with so many forces against him it’s difficult. In this scene, like Lana Wachowski when she was in the real-life subway, Neo finds the bravery to fight for his life and begin accepting himself. As Morpheus says, “he’s beginning to believe”.

While Smith can be seen as the part of Neo that is self-hating and scared, Morpheus is the part that believes in himself. It’s no accident that many of the challenges Morpheus faces are from people who simply ridicule that belief. Just as in real life, transphobia comes in different forms. It’s true that trans people face violent hatred in the real world but we also face more subtle, casual transphobia and doubt from people close to us. Many attacks from transphobes are forms of emotional abuse. Some of the characters in this fictional universe aren’t violently aggressive towards Neo but they clearly have strong opinions about whether or not Morpheus is insane for believing in the One. I’m also often told I’m insane for being trans. If Agent Smith is the part of Neo trying to get him to give up, Morpheus is the part that knows the truth deep down. For me Morpheus represents belief either in yourself or belief and support from others. He picks you up when Smith knocks you down. This is an area where I disagree with others who have written about the trans allegory. Most writers see Morpheus as an older, wiser trans person who gives guidance. (If anyone plays that role I believe it’s the Oracle, who has some answers but insists you have your own story to understand). Agent Smith tells you that what you’re doing is impossible. Your failure is inevitable. When Smith is the voice saying you can’t do it, Morpheus is the voice saying you can.

Why do you persist?

When I started typing this piece I envisaged a well-structured article covering the entire trilogy. Instead it turned into this rambling outpouring of opinions mostly about the first film. I’m OK with that. I see personal pieces like this as entries in a diary of sorts. This is what I think about The Matrix. If anyone else gets something out of it then that’s cool. As a way for me to get my thoughts about the film out of my head, I’ve achieved my goal. I feel I’ve vented. I wanted to bring up a few aspects where I disagree with others and I did that. Mission accomplished. I feel better now.

That said, maybe you want more from this? Maybe I should really dive into the film properly? Maybe I should put my money where my mouth is and cover the continued trans allegory present in the sequels? Maybe. I’ll think about it. If there’s some demand, I could create a series of articles looking at each film individually. I am genuinely surprised that more people haven’t considered the sequels as continuations of the allegory. I’ve tried to watch them and focus on the sci-fi story alone, ignoring any hints of trans stories, and they’re really quite pointless. Perhaps I can help you enjoy them more by providing some of this context in a future entry, because both sequels are infinitely more rewarding when viewed through the lens of the trans experience.

Neo’s journey to become his true self is fantastic but so is his wider journey as an activist fighting for other trans people. I actually like the sequels and the direction they take the allegory. The first film finishes in the most perfect way for a continuation about becoming an activist and fighting for other trans people. When Neo talks directly to the machines at the end of the film, he’s talking directly to the hateful transphobes and people obsessed with enforcing the gender binary.

“I know that you’re afraid… you’re afraid of us. You’re afraid of change. I don’t know the future. I didn’t come here to tell you how this is going to end. I came here to tell you how it’s going to begin. I’m going to hang up this phone, and then I’m going to show these people what you don’t want them to see. I’m going to show them a world without you. A world without rules and controls, without borders or boundaries. A world where anything is possible. Where we go from there is a choice I leave to you.”

I’m not the biggest fan of action films but The Matrix means a lot to me. My friends tell me I’m brave just for being myself. I get death threats because of my gender. I’ve been assaulted for it. I’m violently hated by transphobes including some who stand against racism, homophobia, sexism etc. Every walk down the street requires extreme vigilance. Society seems determined to stop me, just like the forces standing against Neo. This is what makes him a brave hero for many trans people. He could take the easy way out at any opportunity but instead gets right back up every time he’s knocked down. In the climax of the third film, Agent Smith is sure he’s beaten Neo for good only to see him stand up once more. Agent Smith is the worst part of Neo. Deadnaming him again, Agent Smith asks the question that the worst part of me has asked myself far too often in the past:

“You must be able to see it, Mr. Anderson. You must know it by now. You can’t win. It’s pointless to keep fighting. Why, Mr. Anderson? Why? Why do you persist?”

“Because I choose to.”